Wordslöjd & Jargoncraft: an Intern Dictionary of Discovery, Part 3

Intern Jake Fee has written a third installment of Wordslöjd & Jargoncraft: an Intern Dictionary of Discovery. More vocabulary from the world of traditional craft.

Click the link for Part 1 and Part 2

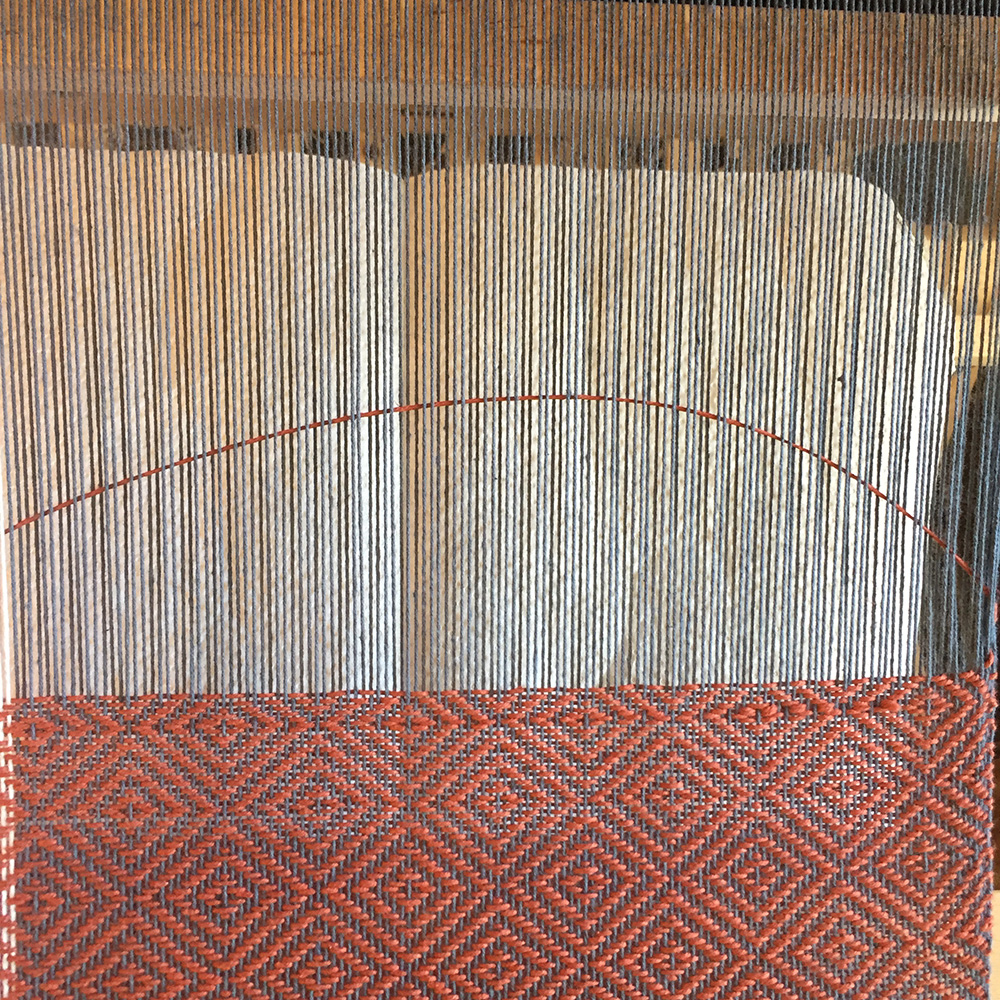

Bubbling. When you thread a weft through a warp, the string does not sit close to the rest of the fabric.

If you're weaving on a loom, you can use a beater, which is more or less a huge comb that smacks down the weft thread into the rest of the piece. If you're weaving by hand, however, pushing your weft thread is more delicate. You bubble. First you push down the middle of the weft, leaving two bumps of unsecured weft.

Then you push down the middle of those two bubbles, making four.

Then on and on until the whole piece is tight. It's this kind of patience which is the hallmark of weaving. Steady, rhythmic, with a pattern that has to be done in the same way each time. I don’t think I’m the only one finding these sorts of rhythms challenging during these times. Time itself is seeming to stretch and wiggle outwards, and normal patterns of work and play are loosening.

The most basic weave is a tabby, also called a plain weave. Over, under, over, under.

This weave is strong and tight, and weaves quick and easy. There is another simple weave, called a twill, which is more hard-wearing and tough. Check out your jeans, or any piece of denim, and you'll see a twill. Because of the lopsided weave - over two, under one, over two, under one - denim is mostly blue on one side and mostly white on the other. That's because denim is made from a white cotton warp and a blue (traditionally indigo-dyed) weft.

Life on campus is inching back towards normality. We had the luck and the pleasure of making some felted-wool projects with Elise Kyllo, an artist in development here at North House. The word felt is surely not a new one to any reader, but I invite you to reflect on how primal that word feels. Felt. What other material have we named after the sense of touch? Or any sense so intimate and direct? The way we talk about felted materials reminds us of its pre-human history; older, most probably, than any other fabric. Each of us three interns made a seat cushion for campus - coming soon to a stool near you - and slippers for ourselves.

Keeping a pandemic-appropriate distance, Elise showed us the process of loose wool fibers meshing and knotting into the strong and ancient fabric. Looking through a microscope, you can see that wool fibers have scaly barbs along their length. When you add hot water and soap and agitation to a fluffy bunch of wool, those fibers crawl towards each other and become locked in place by their backwards-facing barbs. The more hot water, soap, and agitation is added, the more tightly the fibers felt together. Because of all this soapy water, felting is a very hygenic craft for those seeking quarantine-safe activities. The felting process took several days of soaping, agitating, rolling, washing - again, that long-time friend of craftspeople everywhere, good old patience.

Another artist in development, Mike Loeffler, is leading a project that was supposed to be a class: building grindbygg-style timber-framed pop-up shelters for use around campus.

Mike travelled the Swedish countryside learning about grindbygg during his grant-funded artist-adventures in Scandinavia. Back in the good old days, he says, everyone in the country knew how to build a gryndbygg. Before industrialization, which brought professional specialization, anyone walking by a timber frame project could join in and help out - that’s how common this style of shelter-building used to be.

One of many words unique to this kind of carpentry is scarfing. Joining two long timbers end-to-end to form a long, if slightly weak, timber. Weaker, at least, then a single timber of the same length. We’re hard-pressed these days for long, straight, and wide timbers. They’ve all been logged, you see. Wood nowadays is thin, wobbly, and knotty, compared to the towering stacks of lumber that used to be milled from old-growth trees. Perhaps a small silver lining around these lonely days is that the trees have some space to grow more freely. It’s been a long time since we possessed the patience to allow our trees the height and strength that these forests once had.

Anne River Logging Company, 1892, harvesting lumber on the north shore (Sanford C. Sargent (photographer), Minnesota Historical Society)

There is a story from Scandinavian mythology about the beginning of net-making. I do not know how the Scandinavian people started to weave tabby weaves, or knit, or nålbind, but we know who taught them how to make nets, and it was the cleverest of all the gods: Loki. He invented the net and burned his first one - you see, he was hiding out in the form of a salmon from his latest and greatest round of mischief, and he did not want to be caught. I won’t go into what Loki said or what Loki did, because it is unpleasant, and not the kind of story I want to share. I also will not tell you what happened after he was caught - people like Loki always get snared one way or another - because that story leads to war, to earthquakes, to bitter poison and the end of the world. No, I would like to bring your attention to one moment of patience and curiosity in the Norse cycle of myth. The moment after the gods walked into Loki’s home, and found his net burning in the fireplace. Snatching up the charred remains before they fell to ash, the party discovered Loki’s brilliance. He had invented a new weave, a new knot, a new tool for the good of all people. Of course, all the gods were much more focused on catching and punishing Loki than the careers of future fishermen, but they still found themselves impressed. Impressed, and excited, for now they knew how to catch Loki. All of them sat down, the gods and goddesses, clanking with weapons and buzzing with impatient, righteous anger. Even so, they sat down to weave. Patiently bubbling and twilling, or perhaps knotting and twisting, these great beings wove the first nets. Think not of the evil that came before, or the chaos that was to come after. Here, in this moment, I will leave you to admire Thor, and Odin, Frigg and Freya and all the others, radiant in their beauty, sitting on the simple wooden floor, playing patiently with some string.

Stofnun Árna Magnússonar á Íslandi manuscript