Wordslöjd & Jargoncraft: an Intern Dictionary of Discovery, Part 2

Intern Jake Fee expands the Intern Dictionary in a new blog post.

My previous blog post was published just before the COVID-19 situation broke open. Blind to the strange future on the horizon, I left that blog post ready for more personal lessons and one-on-one teaching experiences.

Fingerspitzengefühl. Literally, “fingertip feeling,” a very excellent mouthful of a word taken from the vast wealth of mushed-up philosophy-terms that Germans are so good at coming up with. Fellow interns Nia and Alex went Live on Instagram to learn some birch bark weaving from Birch Bark Beth (alias: Beth Homa-Kraus), but the distance between student and teacher was challenging. What would have been a simple here-let-me-show-you maneuver in person became frustratingly difficult to communicate over a small phone screen. The fingerspitzengefühl of learning craft was totally changed by the global emergency virtualization of work and play.

Can you hear me now? How about now?

Here’s some more vocab: uprights. Those are the up-and-down parts of a basket that can be subtly shifted inwards or outwards by the tension of the weavers. The weavers are, of course, the side-to-side material woven through the uprights, and all together they make up the structure of the basket. We learned this from Ian Andrus, and due to the lonely reality that has eaten up our familiar world, we have yet to finish the baskets we began with him in early March.

Nearly there!

Here’s another: swarf. The junky gunk of steel and stone that builds up like wet sand as you sharpen your blade on a stone. As you can imagine, a sharpening stone filled up with swarf is much too smooth to carve a dull blade into a sharp edge. We interns learned this term from Dennis Chilcote during our masterclass on tool sharpening and blade maintenance - back when those kinds of experiences were still part of our schedule.

Sharpening stones, an abrasive tool, must themselves be abraded every once in a while to remove swarf from the surface.

In the previous post in this series, I wrote about slubs, and how sometimes in spinning the thread of life we will come across a tangled, gnarly, confused mess. What I didn’t mention is that sometimes a slub is so big and hairy and altogether disruptive that your whole spinning wheel will clog and snag and squeak to an abrupt halt. North House, along with the rest of the world, has hit such a slub.

Oh heck.

As interns, during the stay-at-home order we are the lone residents of campus. We are the live-in gargoyles that watch over the buildings and keep the grounds. Instructors, students, staff, and all other craftspeople are home, maybe with the space and materials to keep working, maybe not. As we descend deeper into our digital cocoons, communicating craft becomes much more challenging. Craftspeople are having to become digital storytellers and story-sellers on platforms like Instagram Live and Etsy and Patreon. The hot question on campus is: is it even possible to teach hands-on crafting from far-off virtual distances?

Christine Novotny patiently, virtually walking the interns through setting up a weaving project...

We’re trying. Lots of people are trying. The willingness to jump into this new medium from instructors, artisans-in-development, and staff here at North House is overwhelming and speaks to the incredible community of passionate people that orbit our lakeside school. Even though the world has seemingly slubbed into hibernation, the world of craft spins onward, in any medium possible, in any language that allows it.

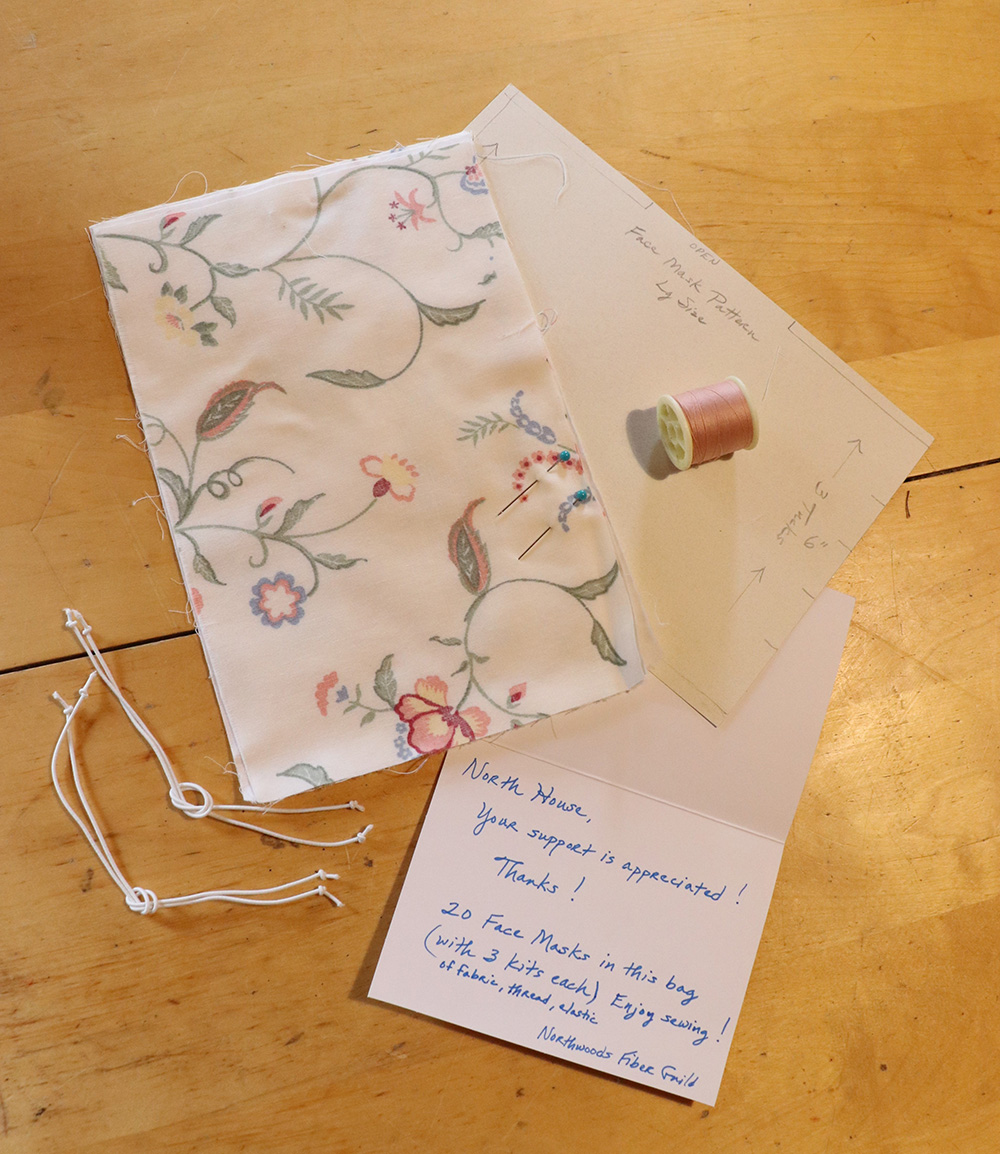

The Northwoods Fiber Guild with a double-whammy preventative care solution that is also a craft-learning kit. Brilliant.

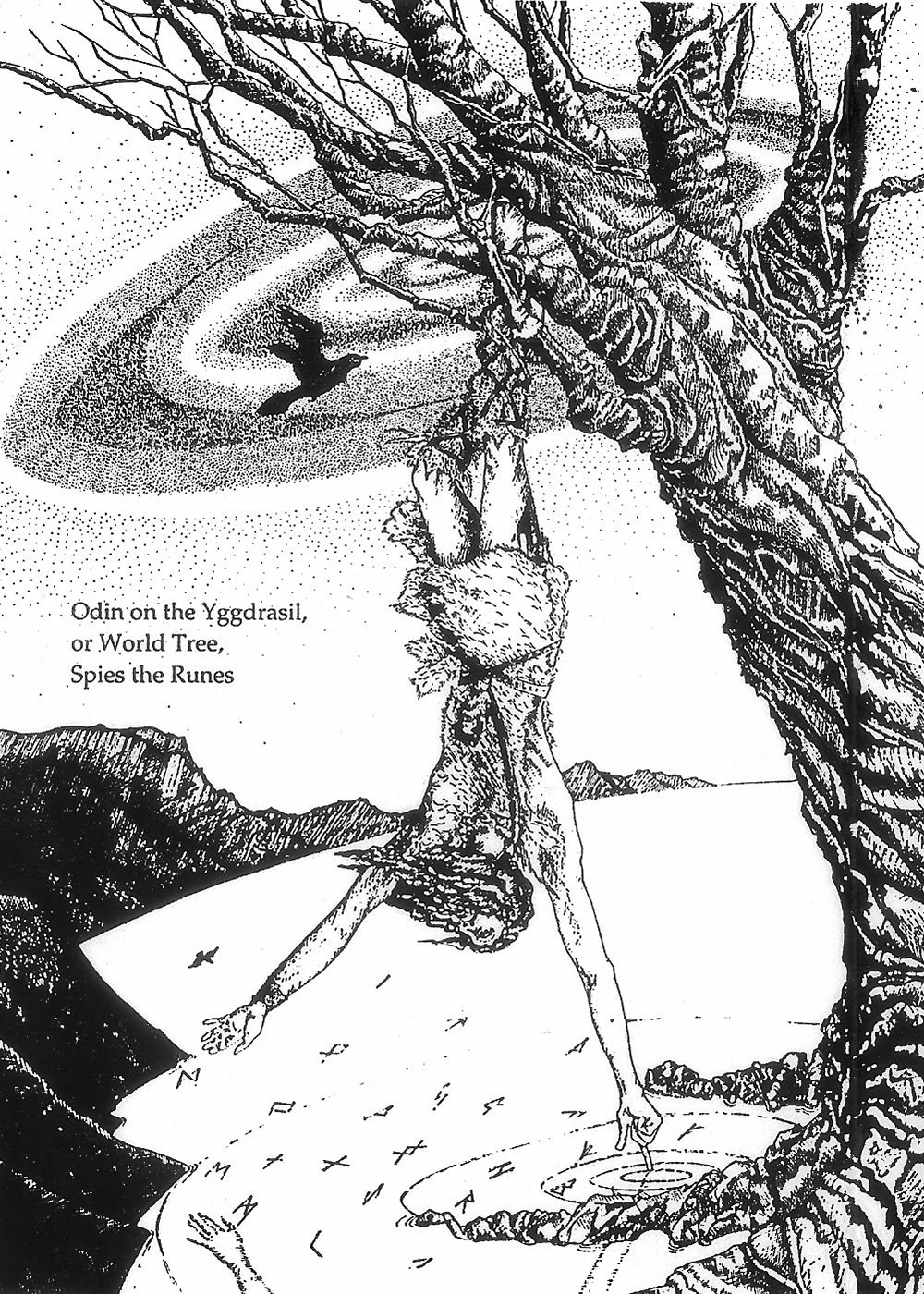

To the ancient Scandinavians, the knowledge of language and craft also grew from a frightening time of near-death stagnation. As the story is told, Odin, the king and father of the gods, took a strong rope and - under cover of darkness - strung himself up from the branches of Yggdrasil, the world-tree. His intention was to secretly watch the Norns - who we have met in the previous blog post - as they authored the fate of the world by carving runic letters into Yggdrasil’s wood. Each word, each letter, directed the making and un-making of every person, place, and thing in the world. Odin is a sucker for secrets, and so he hung in the tree, straining his eyes to see and straining his memory to capture everything he saw. For nine long days and nine cold nights he hung in the tree, starving, thirsting, and freezing, never taking his eyes from the Norns’ secret craft. At last, spent and exhausted and nearly dead, Odin cut himself loose and tumbled back to the world. Though he crawled and limped towards home, looking more like a corpse than the proud king he was, it is said that he came to his house laughing with joy. Through his sacrifice and perseverance, he earned the fingerspitzengefühl of universal understanding: he had learned how to read and write the secret magical alphabet of the Norns. The language of gods! The language of crafting reality itself, and the language to teach it! Collapsing on his doorstep, Odin cried with joy:

I am enriched! I have become wise!

I truly grew and thrived.

From a word to a word I was led to a word,

From a work to a work I was led to a work.

In these strange and lonely days, there are many lessons to be learned, and many new realities at the tips of your fingers. You, like the king in the tree, have earned them all.

Ralph Blum: The Book of Runes