The Golden Spiders of Winter

Spiders are a reminder of the importance of skilled, steady effort. Folklorist Mathilde Yakymets-Lind shares a Ukrainian tale about spiders, and writes about another kind of "spider:" straw and reed mobiles.

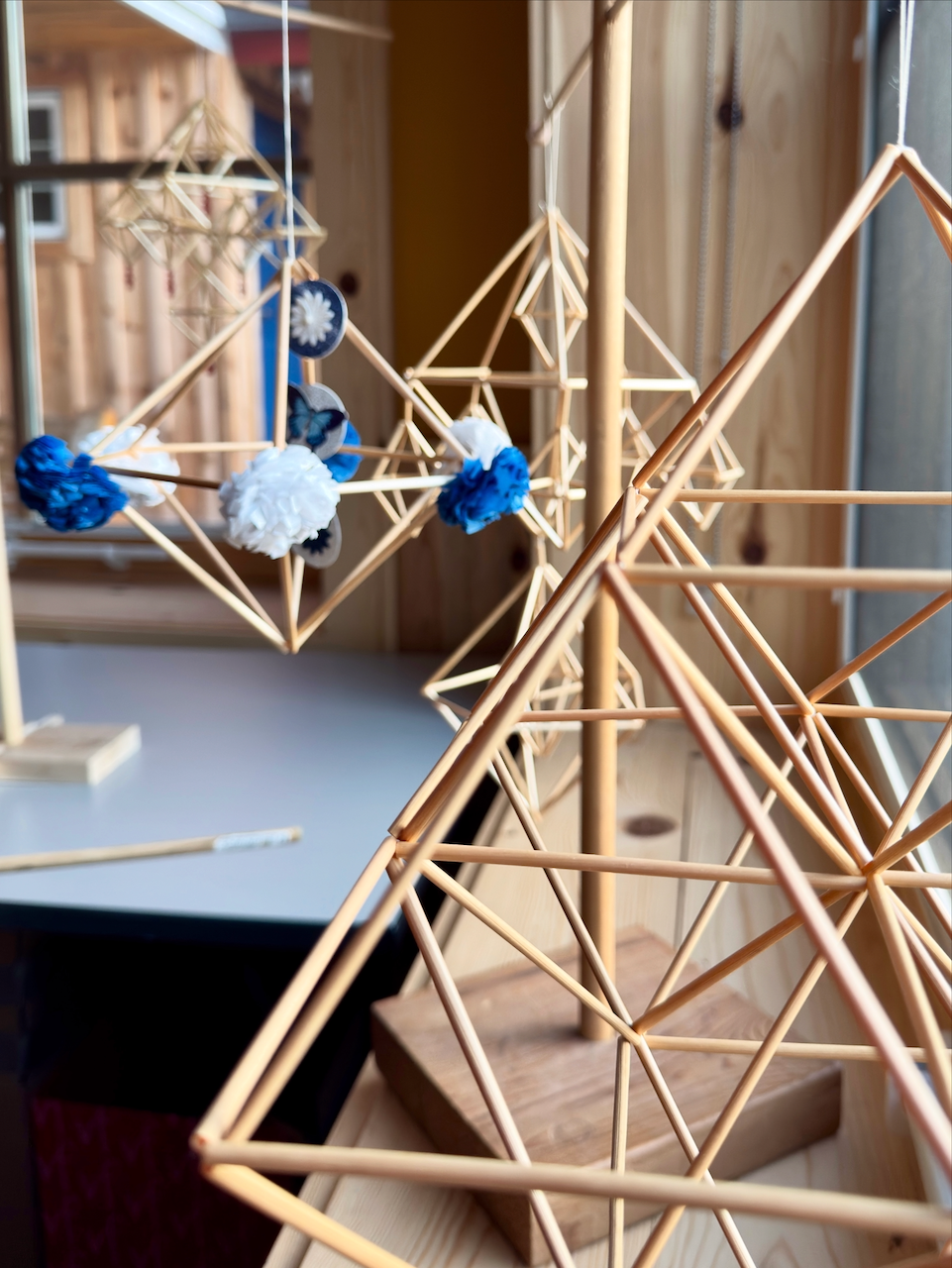

1 Photo above right: Straw mobile made by the author in Mary Erickson's October workshop at North House. Photo by author.

On Christmas Day, I was invited to dinner by new friends in Grand Marais. Everyone was asked to bring a story, but being a folklorist, I was asked to bring a folk tale. I love animals and Eastern European folklore, so I decided to tell a timely Ukrainian story that teaches us to treat all beings with kindness and hospitality: “The Christmas Spiders.” There are many versions of the story, but I told it like this:

There once was a poor family that lived in a small cottage at the edge of the woods. One winter at Christmastime, they brought a little tree into their home. The parents knew they could not afford to decorate the tree, but they hoped it would give the children joy to have it at all.

On Christmas Eve, they heard the children calling them. “Mother, Father, come quickly and look at the tree!”

To their shock, they found that it was covered with spiderwebs. They thought about cleaning it off, but their smallest daughter intervened, saying, “But aren’t the webs beautiful? See how they sparkle? And aren’t spiders God’s creatures too?”

Moved by their child’s kind words, they let the spiders and spiderwebs stay. The next morning, the parents heard the children stirring, and their hearts sank at the idea that they had woken up with hope for decorations and gifts when there were none to be had. Instead, they heard the children calling them as before. “Mother, Father, come quickly and look at the tree!”

Overnight, the webs had turned to silver and gold, and the tree appeared to be covered in glittering tinsel. The family had a beautiful holiday together, then the next day, they gathered up the webs that were the gifts of the spiders for their kindness and hospitality. They were truly made of silver and gold, and the family sold them, which gave them more than enough to stay fed and warm for many years to come.

After reading this tale, it should come as no surprise that having spiders in the home is seen as good luck in Ukraine. They’re the most practical of houseguests, eating small insects and generally keeping to themselves. I have often coexisted with spiders when they’ve taken up residence in a bathroom or some other corner of my home, and as a weaver, I also appreciate the patient precision of a spider weaving its web. We have much in common!

2 Himmeli made by North House instructor Mary Erickson. Photo by author.

Over the past few years, I have fallen under the spell of another kind of spider: mobiles made from straw or reeds throughout Northern and Eastern Europe. They have many names: pavuk (spider) in Ukrainian, uro (unrest) in Norwegian, sodas (garden) in Lithuanian, puzuris in Latvian, rookroon (reed crown) in Estonian, and himmeli (from the Germanic word for heaven) in Sweden and Finland. There are also pająki (spiders) in Poland, a delightfully colorful version that incorporates paper garlands and pom poms (also the subject of an upcoming workshop taught by Britt Malec).

I first encountered these mobiles at Mardilaat, an annual craft market in Estonia. Held around Mardipäev (St. Martin’s Day), the fair showcases the best artisans in the country and includes presentations, awards, and interactive activities. In 2019, I was there for the completion of the world’s largest rookroon, a huge mobile made of reeds (since then, an even larger pavuk has been constructed in Ukraine). I didn’t know anything about these mobiles in 2019, but seeing that massive structure floating in the air ignited my curiosity. I began to dive into the regional traditions and meanings behind them.

3 Näärikroon (New Year's crown) from Osmussaar (Swedish: Odensholm), one of the Aibofolk settlements in Estonia. Photo by author.

As a middling sort of mobile maker, I was self-taught and limited to simple forms. However, I was fortunate that North House hosted a class on himmeli in October, just a month into my residency, and I was able to step in as a classroom assistant. The instructor, Mary Erickson, is a delight; in addition to being a skilled artisan, she is passionate and knowledgeable about the history and culture of himmeli and other similar mobiles. In the class, I constructed two mobiles from straw, one of which I decorated with birch bark beads that I made in an earlier North House workshop with Beth Homa Kraus.

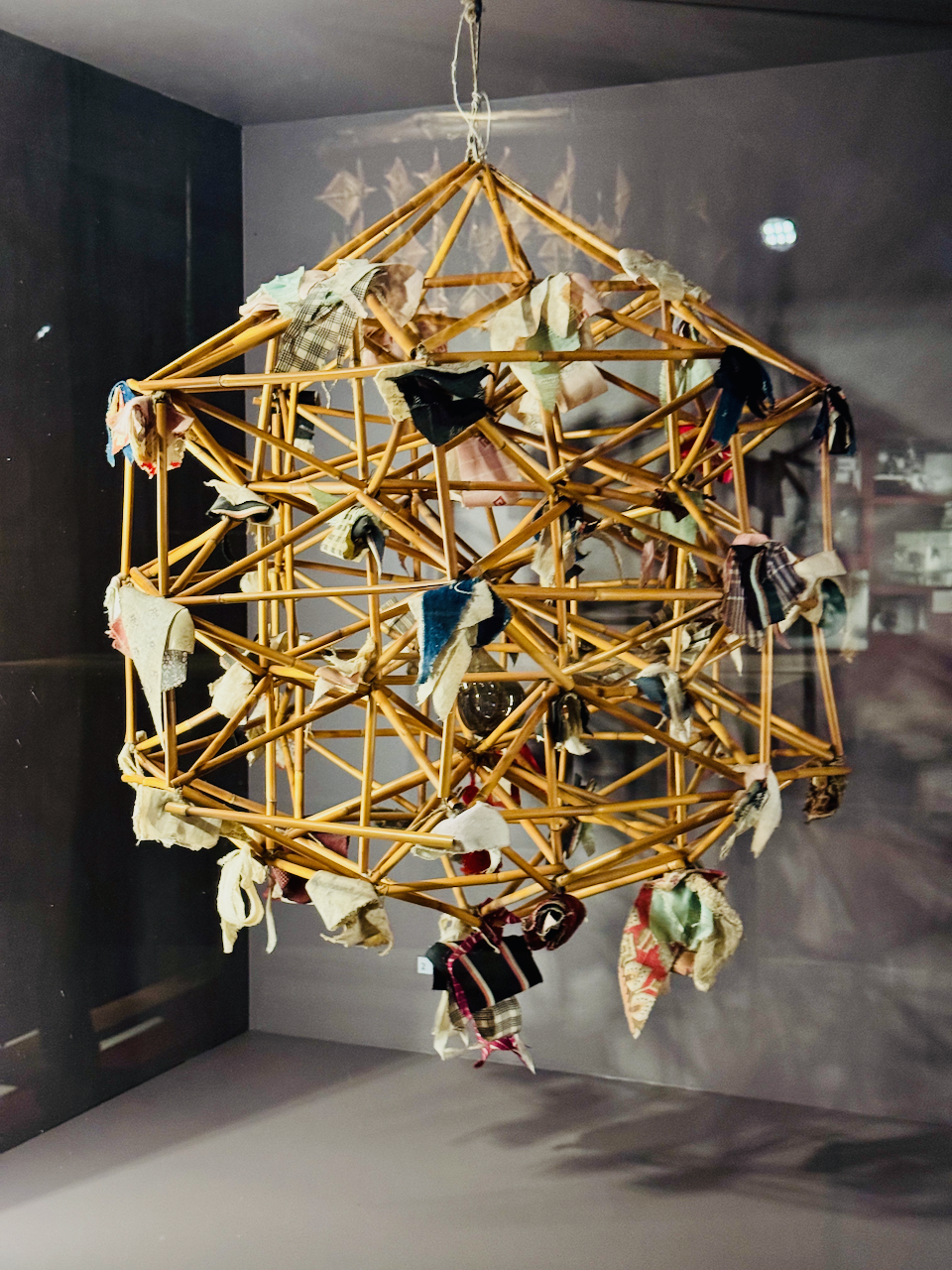

In late October and early November, I traveled to Sweden and Estonia to attend a craft studies conference and do textile research at the Estonian National Museum (Eesti Rahva Muuseum or ERM), and I added another experience to my mobile adventures. ERM is currently hosting an exhibition on the Estonian Swedes (Rannarootslased or Eestirootslased in Estonian, Estlandssvenskar in Swedish, but they called themselves Aibofolk, or island people), free farmers and fisherfolk who lived on the coasts and islands of Estonia for hundreds of years before they were evacuated during World War II. During the violent Russian takeover of several of their islands to build military bases, Estonian ethnographers evacuated extensive collections of handmade objects and accessioned them. When I was doing dissertation research in Estonia, I spent some months researching the material culture of Aibofolk from the Pakri Islands (Rågöarna). There I again encountered mobiles, which were often made of reeds instead of straw. In the current exhibition at ERM, I finally got to see some of these mobiles in person, and they were magnificent! Given the fragility of the materials and the fact that these mobiles were never meant to last (they were usually burned each year), I was awestruck both by their complexity and the good condition they were in. They must be a challenge for museum conservation!

4 Tiny pavuky made by the author.

Inspired by these experiences, I have taken a mobile-making detour in my craft, and I have been experimenting with different materials and scales. I made a batch of simple ornaments for the North House store using brass tubes and red wool tassels; they are small and fairly durable, a little more reasonable to transport and keep than a fragile straw construction. I am currently working on even smaller ones for jewelry. The big challenge is making sure that the joints are neat and consistent, as the beauty of the pavuk comes from its harmony, the many small pieces forming intricate, precise geometric shapes that cast complex shadows as they spin.

I also have been inspired by the different shapes and ornamentation we see in the many local variants of this ancient craft. The record-breaking pavuk in Kharkiv is a great example. Rather than the extremely regular shape of the largest rookroon, it has a swooping, asymmetrical form with many smaller pavuky hanging from it, accentuated with red tassels. I also love the inclusion of fabric scraps and eggs in this halmkrona from Rågö. One of my favorite unusual mobiles was featured in the ERM exhibition. From the aibofolk community of Vormsi island (Swedish: Ormsö), it consists of a sort of wooden wheel from which innumerable gods' eyes are suspended.

5 Rookroon (reed crown) from the aibofolk settlement on the island of Vormsi (Swedish: Ormsö), Estonia. Photo by author.

5 Rookroon (reed crown) from the aibofolk settlement on the island of Vormsi (Swedish: Ormsö), Estonia. Photo by author.

My love of straw and reed mobiles took me by surprise. I usually go in for more practical, everyday crafts, like spinning sturdy wool yarn or weaving commonplace fabric for hardwearing clothing. However, as a folklorist, I find these mobiles fascinating. I love the traditions of bringing a sheaf or even loose straw into the home to ensure prosperity for the coming year. Often, this was the last sheaf (sometimes the first sheaf) of the harvest, which was thought to have magical properties in many different cultures. In Ukraine, such unthreshed ears of grain are tied in decorative bundles resembling a world tree and are called didukh: forefather, grandfather, ancestor. In Norway, straw is scattered on the floor during the Christmas season, and the first sheaf of grain, the julenek, has particular significance. Similarly, in Finland, straw was also scattered on the floor and made into small ornaments representing the sun, moon, and stars. Winter is a traditional time for making mobiles, and they are often burned later at Epiphany (today, as I write this) or even at Midsummer to ensure fertility and prosperity for the coming year. However, many mobiles escaped the flames, and one can find beautiful historical examples in museums across the region.

In Ukrainian folklore, the spider is said to have woven the universe into being, a big job for such a small creature! It’s a good reminder of the importance of skilled, steady labor and the immense work it can accomplish. As we keep to our crafts while the snow falls outside, I find it comforting to channel this spider energy, using the harvest’s plenty to weave golden webs of the promise of spring.