Open Secrets, Tools for Basket Making

It's difficult to make a truly unique basket. Basket making tools, however? That's another story. In this blog post, Ty Sheaffer shows us the many tools they use in their basket making practice.

In a craft as ancient as basketry, it's very difficult to make a truly unique basket. Thousands of generations of people living with astonishing intimacy and knowledge of their bioregional flora have produced baskets of almost every imaginable kind, sometimes independently creating almost identical forms to those of distant cultures on the other side of the planet. Several basket maker friends of mine talk about how they thought they “invented” a specific weaving structure or were the first person to use a particular material, only to open a book years later and see old photos of some amazing examples of the same basket they ‘invented,’ only way better!

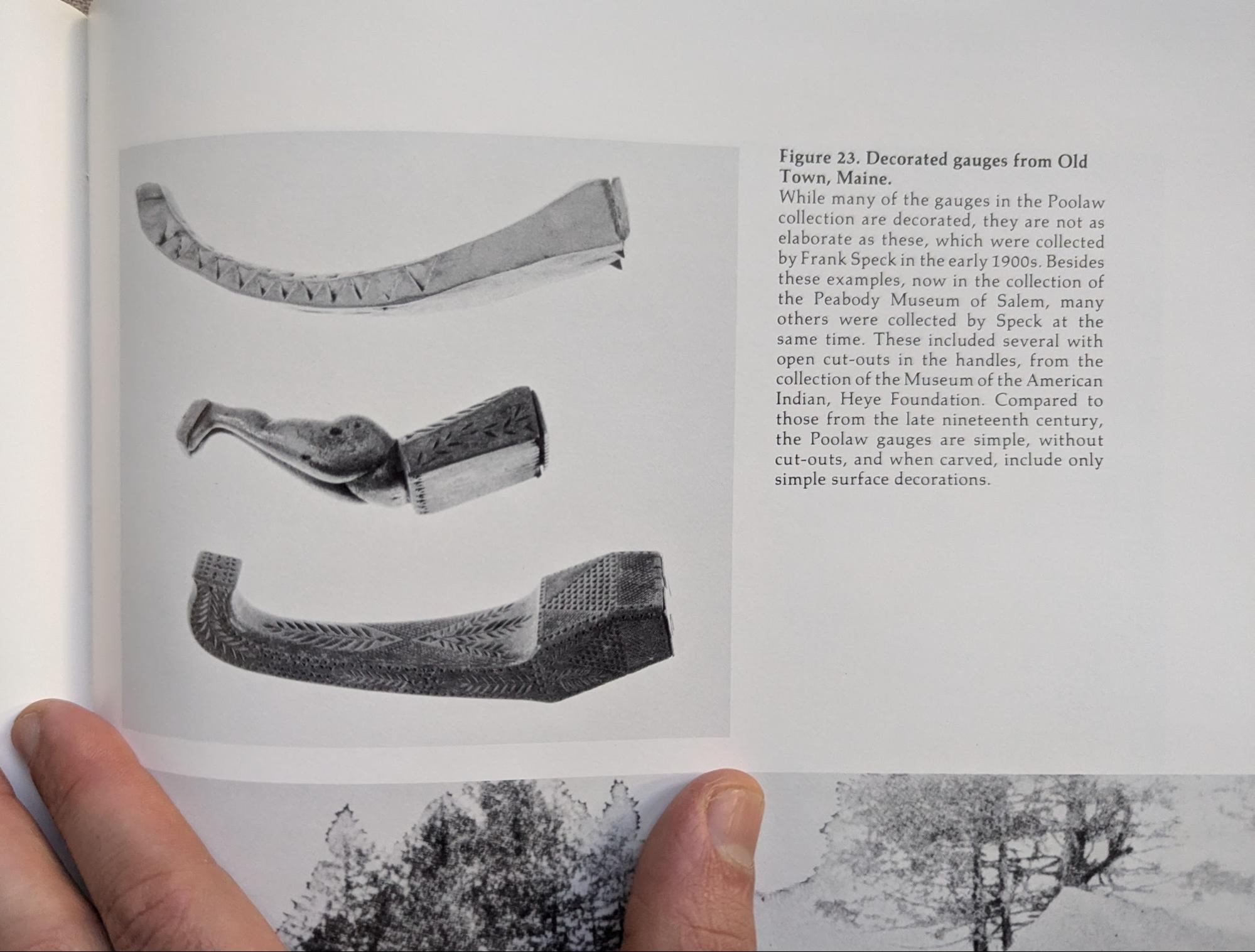

Tools for making baskets are a different story altogether. Basket makers who harvest and prepare their own weaving material often develop their own tools and systems to fit their individual needs and preferences. One of my favorite basket making tools is a splint cutter developed by the eastern indigenous tribes of the Dawn Land on the Northeast Atlantic seaboard. The blades were historically–and still are by some–made by sharpening spring steel from the inner workings of early clocks and embedding and pinning the blades into elaborately chip-carved hardwood handles. Lovely fine ribbons are made by passing thinly split ash over the blades. Wabanaki basketmakers are among those who still make these tools in the way they've always been made and use them to craft their wonderful “fancy” baskets for which they are so famous.

There are a few tools that I've developed myself, others that I appropriated from their intended function, and some that are produced specifically for basket makers. In this photo essay, I'm going to share a few of the tools that I use regularly in my basketry work.

This past year I've gotten into weaving on molds for certain styles of baskets. Inner bark baskets, like the ones in the photo above, can be difficult to weave because the bark often becomes floppy when wet. Soaking the bark, of course, is necessary to make the material pliable enough to weave with. It takes skill and experience to be able to control the shape of a basket; when the material is noodley, it’s nearly impossible to precisely control it without using some type of form or mold.

Various molds I made in 2024.

Various molds I made in 2024.

The bottom twill section of this basket was woven on a mold, then removed, and the twinned border at the top was “free woven.” The transition from the bottom to the sides can be tricky for beginners. I think it's a good idea to have folks new to weaving use a mold at least for this transition, so they can just focus on weaving and not worry about getting the tension right.

I cut basketry material into strips in a few very different ways. The classic approach is with a knife or scissors. This approach is certainly best if you have bark or splints that have little defects that you need to work around–cracks, pin knots, etc.–and results in little waste compared to other methods. Often the simplest tools require the most skill, and using a knife or scissors is no exception, especially when making very uniform, narrow widths. These are my favorite handmade Japanese scissors. They're sturdy, elegant, easy to sharpen, and can cut through thick, tough bark.

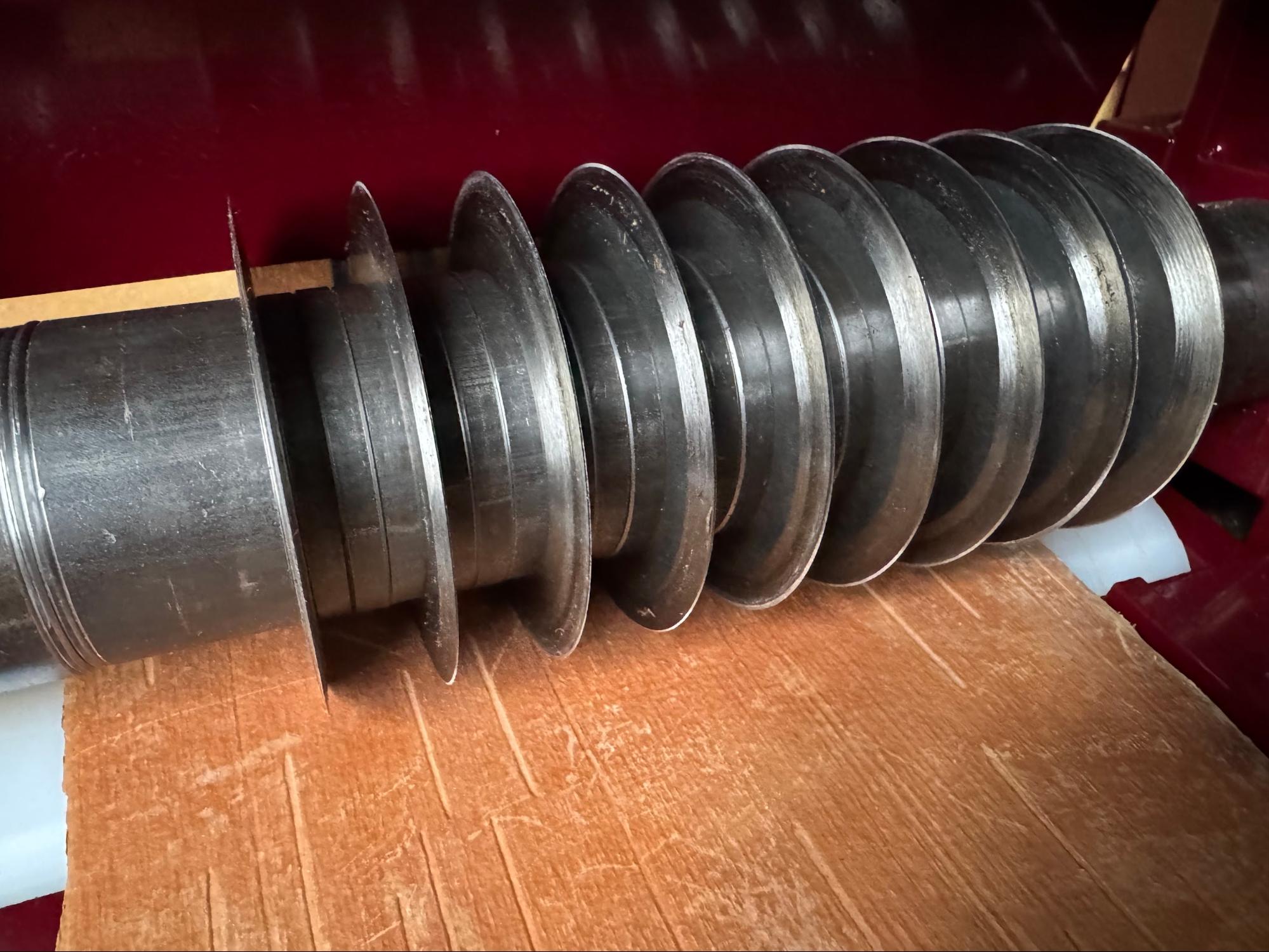

This tool is at the opposite end of the spectrum for cutting splits. It's actually made for cutting leather but works well for all kinds of bark, including birch bark, and can cut widths down to an eighth of an inch.

Crank the handle, out comes birch strips!

I certainly wouldn't recommend getting one of these unless you're cutting loads of material for teaching classes or are a basket weaving maniac.

The humble fid, also known as a kostyk in Russian, is the indispensable tool for nearly every type of basket I make. They are used to pry under previously woven sections in order to tuck and splice in new weavers. These were hand forged by my friend Lucian Avery in Vermont, and I just finished turning and hafting the handles. This little collection is for students to use in my upcoming classes!

For bark basketry I use these flat nose, copper electrical clips. They last way longer than any other clip I've tried and are narrow enough to use in fine work.

These Japanese thread shears, Nigiri Basami in Japanese, are a relatively new addition to my basket kit. They are great for cutting in tight spaces and can cut very close to a surface, as in when cleaning up all the little stray bits when a basket is complete. You only use the tip to cut, which is thinner than any other scissors I'm aware of.

Once the bark is cut into strips, it often needs to be thinned down. Having material that is a consistent thickness is important for making a nice, balanced basket. For years I split all the material I worked with by hand, and still do for some species. The tools in the photo above are leather skivers and, when the conditions are right, can make very nice, uniformly thick weavers with little effort. They use a thin razor blade to slice the material which can create a totally different look than when one hand splits, often shinier with more of the neat characteristics of the bark becoming visible, like the way planing rough wood can reveal the grain pattern.

Oiling a basket can be a contentious topic among weavers. These days, I do so more often than not, and my go-to is made by Heritage Natural Finishes. I've been using the liquid wax as a lubricant while weaving birch bark and the original recipe for finishing inner bark baskets. All their formulas are slight adjustments on a simple combination of linseed oil, tung oil, pine rosin, beeswax, and a little orange oil. Some basketmakers finish baskets with encaustic wax to give them more structure. The drying oils in Heritage add some rigidity and strength, while allowing the basket to maintain flexibility. I don't recommend using oils that don't harden, such as olive oil or mineral oil because they attract dirt and can spread oil onto things.

Ty Sheaffer teaches basketry classes at North House Folk School. Find all upcoming basketry courses here!