Making Japanese Sukumo Indigo Vats for North House, Unplugged 2025

This fall, Kenta Watanabe (Japan) taught sukumo indigo dyeing at North House. But in order for class to happen, someone local had to prepare the dye vats. In this blog post, Jazmin Hicks-Dahl shares the process she used to carefully prepare the living dye for class.

Can you share a little bit about your own background with indigo dyeing? How long has indigo been part of your craft practice?

I fell in love with indigo textiles in my teens. I used to visit a shop called Kasuri Dyeworks in Berkeley that was filled with rolls of indigo dyed kimono cloth. Over the years I have collected indigo textiles and dabbled in growing and dyeing with indigo. In the past six years, I have had the opportunity to really focus on indigo dyeing.

In 2018, I visited Arimatsu, Japan, where shibori (Japanese tie-dye) has been practiced for hundreds of years. Shibori is commonly paired with indigo dyeing to make the patterns. That year, I also took a class at North House about dyeing with Woad, the European form of indigo.

In 2019, I took more classes. I learned how to dye weaving yarn with Japanese indigo, make katazome stencil resist patterns, create a variety of shibori patterns, and make sukumo indigo with composted leaves. I also began dyeing in different kinds of indigo vats—fructose, henna, iron, madder fermentation, urine! and sukumo.

My current focus is on indigo dyeing bound threads to make ikat patterns and handweaving them.

Rolls of shibori in a shop in Arimatsu, Japan, 2018

Examples of my work:

.jpeg)

Spoon Scarf, indigo dyed katazome stencil resist, Jazmin Hicks-Dahl, 2019

.jpeg)

Triangles Scarf, indigo dyed shibori, silk/cotton, Jazmin Hicks-Dahl, 2020

.jpeg)

Ikat Dishtowel II, handwoven indigo dyed linen thread, Jazmin Hicks-Dahl, 2020

Su-ku-mo—pronounced “skooo-mo”—is the word the Japanese use for compost made from Persicaria Tinctoria indigo leaves. This special dirt is the pigment and starter for fermentation vats that dye cloth blue. Making sukumo is a year-long process beginning with planting the seeds, growing the plants, harvesting the leaves, and creating the compost. I learned about this cycle from Kenta Watanabe, indigo dyer and farmer from Japan, who came to North House Unplugged 2025 as a guest and instructor.

Sukumo from Watanabe’s indigo kit—it is the starter, the dyestuff, and the food for the vat.

How did you get connected with Kenta (and with the job of preparing the sukumo dye vats) ahead of his visit?

Yoshiko Wada was one of the teachers I had at a shibori intensive workshop on Madeline Island. She had also co-owned that Japanese textile shop in Berkeley. I introduced her to Jessa Frost, North House's Program Director, when we were on the search for a Japanese textile artisan to come to Unplugged. Wada leads the World Shibori Network Foundation and is connected with many Japanese textile artisans. Kenta was already coming to the US for a WSNF event, so it turned out to be perfect timing.

I realized in order for the workshops to happen, someone local would need to make the sukumo vats for the classes. Since I had some experience with sukumo, I offered to make them. I looked forward to learning from Kenta, and I was super excited to support North House and be involved with the whole event.

All North House courses involve prep work, but this one was extensive! Can you give us an overview of the process you used to prepare the dye vats?

Because indigo is not a water-soluble dye, in order to dye cloth with indigo, you have to transform it by making a vat. In the vat, the pigment (either as a powder or from the plant leaves) is transformed through fermentation or chemical reduction into a yellowish liquid that is now soluble and able to penetrate cloth. After the cloth comes out of the vat and has contact with air, it slowly transforms back from yellowish to greenish to indigo blue. There are many recipes for making a vat. In Japan, sukumo vats are the tradition.

A freshly made sukumo indigo vat.

Making a sukumo vat is not hard, but there are many steps and no shortcuts can be made.

Here is the basic process for making sukumo vats according to Kenta Watanabe’s instructions:

- Make wood ash lye from the ashes provided in the kit and hot water.

- Mix sukumo, hot water, wood ash lye, wheat bran, and shell lime (specific measurements are given depending on the size of your kit)

- Keep your container warm (I used a seedling heat mat)

- Maintain your vat daily (twice a day at the beginning):

- Check PH

- Check temperature

- Dye a test strip

- Fill out the recording sheet

- Make adjustments as necessary

- Stir the vat

After a few days, the vat should begin showing color. If you did it right, after two weeks the fermentation is fully developed and the vat is ready to dye. Shinya, Kenta’s assistant, described the process as caring for babies. They need warmth, nutrition, and daily monitoring.

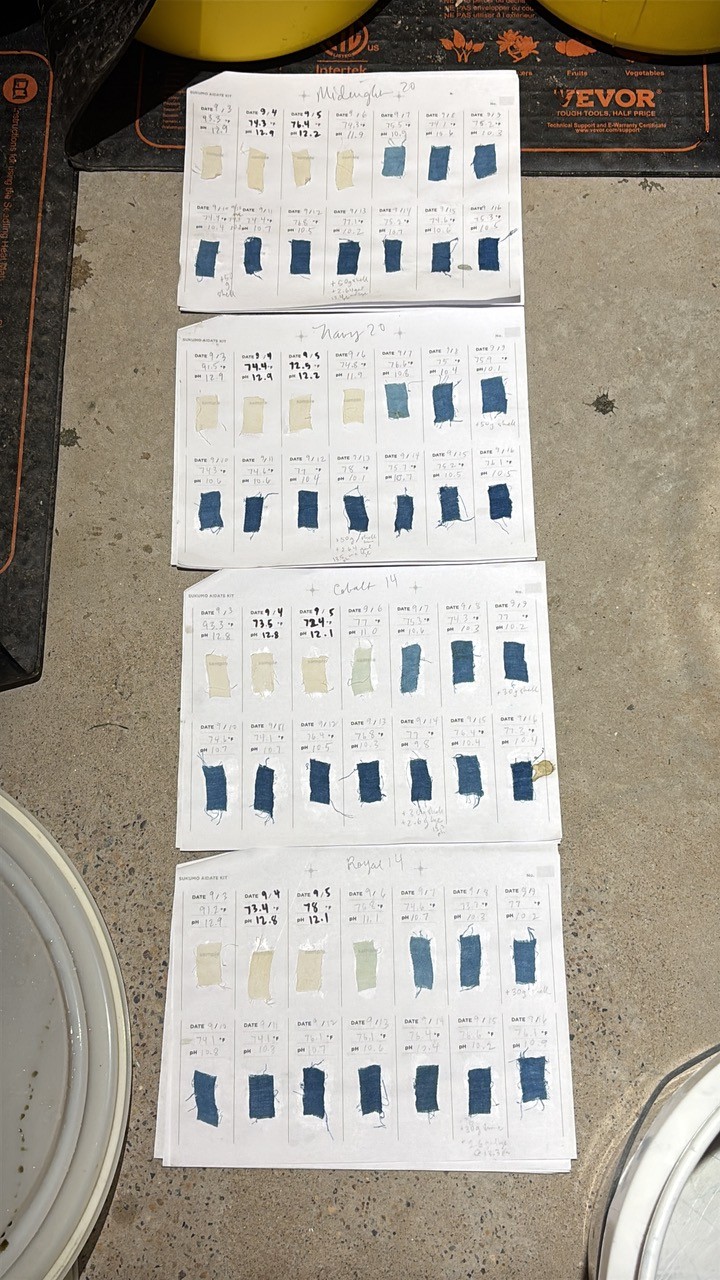

The log for the North House sukumo indigo vats.

How long did this process take, and when did you start? Did you work with Kenta as you went?

I started training 6 months before the courses at North House (sounds like training for a marathon!). Kenta sent me a couple of mini sukumo kits, a product he is developing with WSNF to introduce sukumo indigo dyeing to Americans. I joined a test group to trial these 1 liter “mini-kits.” We made the kits together on Zoom and followed up with daily reports and photos of my log via Whatsapp for several months. Kenta was ready to answer any questions and troubleshoot problems.

It was challenging to stick to this routine, but an important exercise in understanding and appreciating the needs of this living being of bacterias that makes a sukumo indigo vat. Each day was different—the smell, the surface, the texture of the liquid, the color of the test strips. Logging everything helped me notice those subtle changes. If anyone has worked with fermentation, you will know that the process is very dynamic and literally changes with the weather.

I made two mini-kits and then I scaled up to a small size kit (5 gallons) and repeated all the same procedures, including sending in daily reports. Everything was going smoothly, and the vats were giving color as expected. Not all the other trial group members had the same success. Some had problems with chlorinated water, container shape, heat fluctuations, and PH problems.

A month before Unplugged, I collected the equipment for two 14-gallon and two 20-gallon vats and began making wood ash lye. I was definitely intimidated by making 4 big vats all at once. I worried that if the vats failed, there would be no way to fix them. I would have wasted precious sukumo, and at least 60 students would be depending on me! I couldn’t let them down…

My husband and I considered the best place to make the vats. The smell was a big consideration—a cross between barnyard and steaming compost pile. Jarrod said, “In my woodshop? No way!” We had to make sure it was accessible to the back of his truck, so no going up our basement stairs. We had to minimize temperature fluctuations too, so we settled on the well-insulated dust collection closet.

My sukumo babies

Two weeks before Unplugged 2025 Cobalt, Royal, Navy, and Midnight, my indigo babies, were born—in the sawdust closet. Kenta-san was not too concerned with the vats for the weeks before Unplugged. He was busy in New York, and maybe he trusted me by then? I sent in reports less frequently. My babies grew healthily.

Once the dye vats were ready, how did you transport them to North House?

Jarrod made a makeshift ramp with two Douglas Fir 2x12’s, and we rolled them up into the back of the truck. I had bought hazmat containers that came with locking lids to prevent spillage during the 4-hour drive. On the way to North House, I picked up Kenta and WSFN translator Tomoko Ferguson from the shuttle stop in Duluth in my car. I watched the vats at the back of Jarrod’s truck the whole way. When we arrived at North House and brought the vats into the classroom with the forklift, Kenta opened them, smelled them, stirred them, and pronounced them good… What a relief!

The vats traveling through Duluth.

What was it like seeing the sukumo dye being used by students in class?

It was like sukumo indigo went viral on campus! People were totally mesmerized by the dyeing experience. Maybe it is because the vats are alive (with bacteria), that it is so easy to get attached to them. Working with the vats, dipping cloth into them, seeing that color emerge—it is an addictive experience. It was great to see blue fingers and fingernails, something normally perceived as strange—not to mention stinky—became a status symbol on campus and around town. It was a secret sign that only the sukumo initiated knew about. Unplugged guests sported their fashionable shibori neck bandanas, and students even said they would miss the smell when class ended.

I felt extremely satisfied that the vats were strong and able to dye so many students' work over the course of the week. I also felt like people finally understood my obsession with indigo. They understood the process because they had experienced it. I could see that Kenta’s mission to connect people with sukumo indigo was being fulfilled.

4-day indigo dyeing workshop participants

Is there anything else you'd like to share about being part of this experience?

I feel so lucky to have been at the right place at the right time to work with Kenta and his sukumo—something so rare in the United States. The time spent learning about and maintaining the vats was joyful work. I am glad I could contribute to North House in this way. Sincere thanks to everyone at North House, the students in the indigo classes, Jessa, Kenta, Shinya, Tomoko, Yoshiko, the mini-vat test group, and Jarrod for their help.

Kenta and Jazmin at North House Folk School

Jazmin Hicks-Dahl runs Woodspirit Handcraft & Woodspirit School of Traditional Craft in Ashland, WI with her husband. She studied indigo dyeing with Takayuki Ishii and shibori with Hiroshi Murase and Yoshiko Wada in 2019. She makes indigo dyed textiles, both stitched and handwoven. She spent eight years teaching children in the SF Bay Area where she grew up before moving to the Northern lands. Her background includes art & design, a love of natural materials, folk textiles, and an obsession with indigo since her teens. Instagram: @loveblueindigo

Watanabe’s Sukumo Indigo Kit: https://watanabes.jp/en

World Shibori Network Foundation: https://shibori.org/