Sweden's Craft Consultants and the Value of Handcraft

In Sweden, craft consultants support professional craftspeople and engage local communities in craft education. Jake Fee writes about their work and poses a question—what would the Midwest look like if we had craft consultants here?

There is a special kind of job in Sweden, a position that does not (yet!) exist here in Minnesota: o, be ye in awe of the Craft Consultant! Attached to regional governments, museums, or schools, craft consultants engage their local communities in craft education and practice.

A great joy of our trip was meeting with the craft consultants associated with the Västernorrlands Museum in the city of Härnösand. As you can see, we geeked out about knitting together with a large group of wonderful local fiber freaks. It was a splendid day of slöjd.

We learned that craft consultants have two goals: to raise the general level of craft skill in their community, and to support professional craftspeople working at a very high skill level. Our entire group was wowed by the idea of a government setting aside funds to support craft traditions. Could you imagine!

Perhaps naively, I had assumed that craft consultants and government-funded hemslöjd (hand-craft) projects were in the realm of cultural protection and traditional heritage. Not so! In fact, we were told that hemslöjd education was actually a strategy of economic resilience for rural people in Sweden.

At North House Folk School, as our mission statement so elegantly states, craft is the mechanism through which we build community. A strong community is our primary joy, and craft is how we get there. This is not exactly the case, historically, for craft in Sweden. As a poor country with thin soil, Swedish folk needed more than just agricultural revenue to stay self-sufficient. Thus: the craft consultant. What better way to make an extra buck than to spin, weave, paint, knit, carve, forge, embroider?

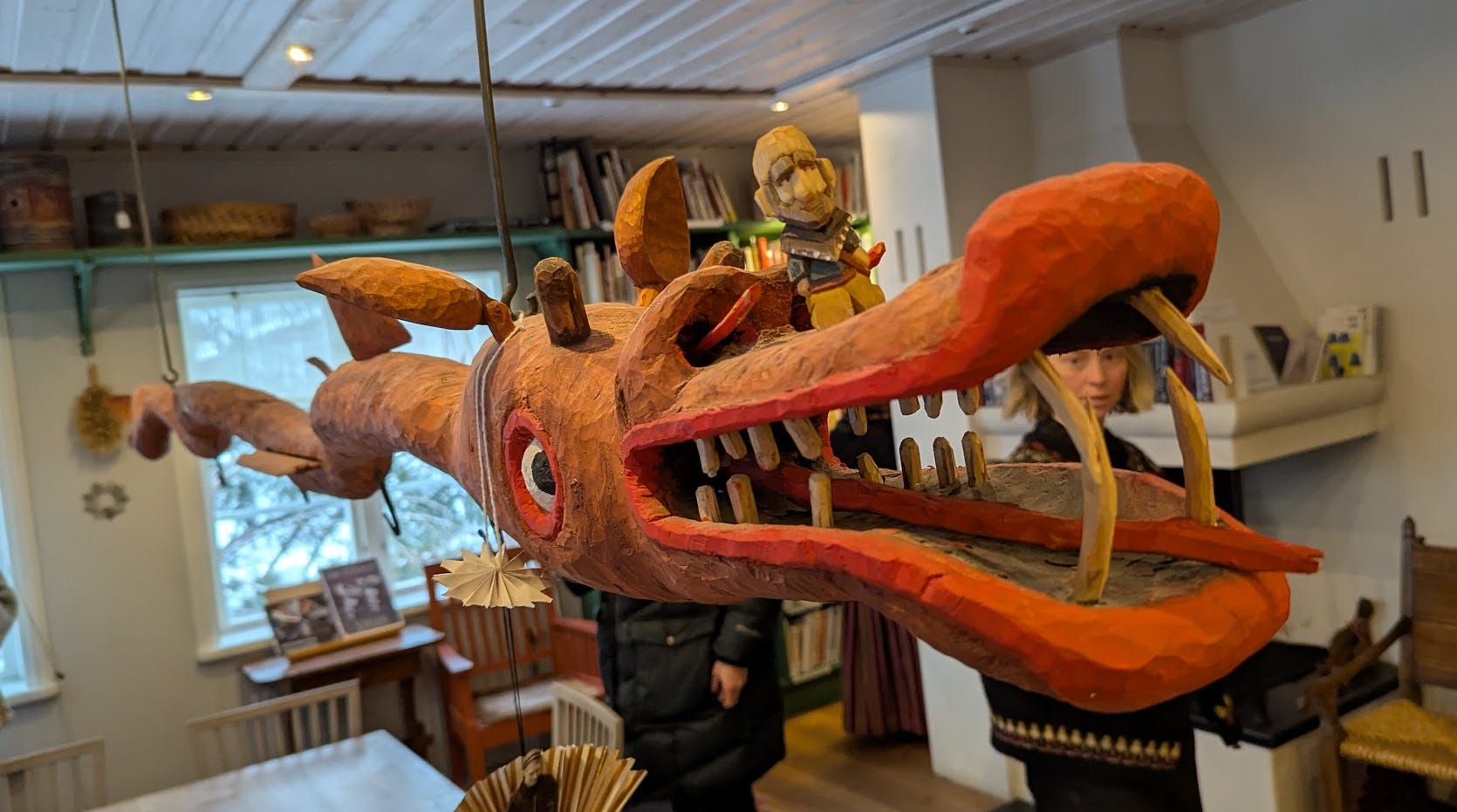

The Dala Horse, for example, was an economic invention for rural people to support themselves with an accessible craft. Anyone can learn to carve and paint a Dala Horse, and the country leaned into the horse as a symbol, and there you have it: a sustainable side hustle for anyone with a knife and a paintbrush, supported by craft consultants, encouraged by the public use of the Dala Horse as a semiotic lure for attracting tourists.

The region of Dalarna, we learned, especially thrived from craft. Different villages had their own specialties, such as coopering barrels, weaving bands, or knitting mittens. People would travel to Stockholm and beyond to sell their crafts in order to support their families. In this way, Dalarna became a nucleus of craft traditions in Sweden, which is still true today.

I wonder what a modern Midwest might look like if we had similar craft programs. More handknit sweaters, more handcarved spoons, more handforged knives. You could be forgiven for thinking that an acrylic sweater from Walmart or Target is cheaper than a handmade woolen sweater from a local sheep. But in fact, just like buying paper plates rather than nice ceramic dishware, the cheaper option is more expensive in the long view. Wool rarely needs to be washed, and acrylic yarns have a particular talent for absorbing armpit smell. Wool becomes stronger over time, and can be easily repaired, while acrylic yarn sheds microplastics and weakens in structure very quickly.

This is true of many materials and many objects. Wooden chairs last longer than plastic chairs. Wooden spatulas make more delicious food than silicon spatulas. Leather burnishes beautifully over time, while rubber crumbles into crusty crumbs.

During this trip to Sweden I was repeatedly reminded that well-crafted objects made from natural materials are not luxuries, or empty eco-conscious virtue-signals, or antiquated historical artifacts. Not at all. Beautiful objects are good investments in yourself and in the future of the world.